Remote Camera System for Hazardous Machining Tasks

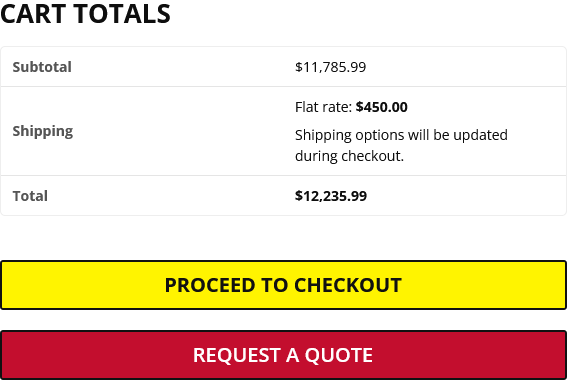

$2,995.00

Remote Camera System for Hazardous Machining Tasks

Remote Camera System for Hazardous Machining Tasks lets machinists safely view setups, tool touch-offs, and finish verifications without entering the point of operation. Includes a waterproof camera with LED lighting, 16-foot cable, 11″ monitor, and mounting hardware.

Not sure where to start? Reach out to our team to learn more.

To request more information about this product or service, please complete the form below. You can also chat live with one of our specialists via the widget in the bottom-right corner of your screen or call us at (574) 318-4333.

Remote Camera System for Hazardous Machining Tasks

Increase operator safety and machining precision with the Remote Camera System for Hazardous Machining Tasks. This innovative camera and monitor kit lets machinists view tool setups, touch-offs, and surface finishes in real time—without stepping into hazardous points of operation. Ideal for lathes, mills, grinders, and other enclosed or guarded equipment where visibility is limited.

Key Features

- 16-Foot Camera Cable with LED Lighting: Bright, adjustable illumination ensures clear visibility in any machining environment.

- Compact Waterproof Camera: 1/4″ diameter x 1″ length camera withstands coolant spray and chips.

- 11″ Operator Monitor: Provides a large, high-resolution view of your machining area for precise tool adjustments and finish verification.

- Monitor Mount: Secure and adjustable mount keeps your display easily accessible to the operator.

- Toolholder Camera Mount: Enables quick and accurate positioning directly on the toolholder for maximum visibility.

Applications

This remote camera system is perfect for:

- Machinist setups and calibration

- Tool touch-offs and part verification

- Observing cutting operations without exposure

- Improving compliance with OSHA 1910.212 and other machine guarding standards

Benefits

Designed to improve both operator safety and production efficiency, this system allows continuous monitoring of machining operations from a safe distance. It helps prevent accidents, reduces downtime, and gives machinists full visual control over their processes—without interrupting protective guards or opening doors.

Specifications

| Component | Specification |

|---|---|

| Camera Cable Length | 16 feet |

| Camera Size | 1/4″ diameter x 1″ length |

| Lighting | Integrated LED |

| Monitor Size | 11 inches |

| Waterproof Rating | Yes – Coolant-resistant |

Order Your Remote Camera System

Protect your machinists and streamline setup procedures with the Remote Camera System for Hazardous Machining Tasks. Built for durability, clarity, and safety—engineered by ODIZ to support safer machine operations and compliance with industrial safety standards.

1910.212(a)(1) - Types of guarding

OSHA 1910.212(a)(1) — General Duty to Guard Machines

OSHA 29 CFR 1910.212(a)(1) establishes the primary obligation to guard machinery in general industry.

It requires employers to implement one or more methods of guarding that protect both the operator and nearby employees from hazards created by points of operation, rotating parts, flying chips, sparks, or any other dangerous mechanical motions.

Scope and Intent

This paragraph serves as the foundation of all machine guarding enforcement.

It mandates that every machine presenting a mechanical hazard must be safeguarded through a combination of physical barriers or engineered safety devices.

The employer may choose the guarding method, but it must completely prevent employee exposure to the moving part or hazard zone during normal operation.

Acceptable Guarding Methods

- Fixed guards: Rigid barriers that prevent access to hazardous areas.

- Interlocked guards: Guards that automatically shut off or disengage the machine when opened or removed.

- Adjustable guards: Barriers that can be positioned for different operations but remain securely in place during use.

- Self-adjusting guards: Guards that move automatically into position as the operator works, covering the danger area as material is fed.

- Electronic safeguarding devices: Light curtains, pressure-sensitive mats, and presence sensors that prevent access to moving parts.

Key Compliance Requirements

- Guarding must protect both operators and nearby personnel.

- Guards must be securely attached and durable enough to resist normal operation and vibration.

- Openings in guards must be small enough to prevent accidental contact with moving parts.

- Guards must not introduce new hazards such as sharp edges, pinch points, or visibility obstruction.

- All guards must be kept in place and functional when machines are operating.

Common Violations

- Machines operating without guards over exposed belts, pulleys, gears, or shafts.

- Removed or bypassed barrier guards during production or maintenance.

- Improper guard materials or openings that allow hand or finger access to moving parts.

- Lack of guarding for nearby employees who may be struck by flying material or sparks.

Practical Compliance Tips

- Conduct a full hazard assessment for all equipment to identify points of operation and motion hazards.

- Install fixed guards wherever possible; use interlocked or adjustable guards only when process requirements demand it.

- Include guarding checks in your preventive maintenance program.

- Train operators to recognize unsafe conditions and never remove or modify guards.

Why OSHA 1910.212(a)(1) Is Important

This paragraph represents OSHA’s general duty clause for machinery safety.

Most machine-related injuries occur when guards are removed or missing, and OSHA 1910.212(a)(1) gives inspectors the authority to cite any unguarded moving part that poses a risk.

Compliance ensures that workers remain protected from crushing, entanglement, amputation, and impact injuries.

FAQ

What types of hazards must be guarded under 1910.212(a)(1)?

All hazards created by points of operation, rotating parts, nip points, or ejected materials must be guarded or otherwise controlled.

Can presence-sensing devices replace physical guards?

Yes, when properly installed and tested, electronic devices such as light curtains can serve as equivalent safeguards if they prevent operator exposure to motion hazards.

Is 1910.212(a)(1) only for operators?

No. Guards must protect both operators and nearby employees who could be injured by machine movement or flying debris.

1910.212(a)(2) – General Requirements for Machine Guards

OSHA 1910.212(a)(2) — General Requirements for Machine Guards

OSHA 29 CFR 1910.212(a)(2) establishes the design and construction standards for machine guards.

This provision requires that guards be securely fastened to the machine and designed to protect operators and nearby employees from injury caused by moving parts, flying debris, or accidental contact.

The intent is to ensure that guarding not only provides protection but also does not create new hazards in the process.

Key Guard Design Requirements

- Secure Attachment: Guards must be firmly attached to the machine. If fastening directly to the machine is not possible, guards must be securely mounted elsewhere to provide equal protection.

- Structural Integrity: Guards must be made of materials strong enough to resist impact, vibration, and normal wear during operation.

- No New Hazards: Guards must not introduce additional risks such as pinch points, sharp edges, or visibility obstruction.

- Durability: Guard materials must withstand operational stresses and environmental factors like heat, coolant, or debris.

- Accessibility: Guards should allow safe maintenance, lubrication, and adjustments without requiring complete removal when possible.

Performance Intent

The focus of 1910.212(a)(2) is performance-based guarding design.

OSHA does not prescribe specific guard materials or thicknesses; instead, the guard must perform effectively under real-world conditions.

Employers have the flexibility to design guards suited to their machines—as long as the guarding prevents contact and remains in place during operation.

Examples of Guard Types Covered

- Fixed guards enclosing belts, pulleys, gears, and rotating shafts.

- Interlocked guards that shut off power when opened or removed.

- Adjustable guards for variable-sized stock or cutting operations.

- Self-adjusting guards that move automatically with the workpiece.

Best Practices for Compliance

- Inspect guards regularly for looseness, cracks, or corrosion.

- Use guard materials that match the operational environment (e.g., metal for high-impact areas, polycarbonate for visibility).

- Train employees to recognize damaged or missing guards and to report deficiencies immediately.

- Ensure all guards are reinstalled and secured after maintenance or adjustments.

Common Violations

- Guards loosely attached or easily removable during operation.

- Improvised guards made from inadequate materials such as thin sheet metal or plastic covers.

- Guards with sharp edges or openings large enough to allow finger or hand access.

- Removed or bypassed guards not replaced before restarting the machine.

Why OSHA 1910.212(a)(2) Is Important

Even when a guard is present, poor design or weak construction can fail to protect workers.

OSHA 1910.212(a)(2) ensures that guards are engineered and maintained to perform effectively throughout a machine’s life cycle.

Properly designed guards prevent crushing, amputation, and laceration injuries while maintaining usability and productivity.

FAQ

What materials are acceptable for guards under 1910.212(a)(2)?

OSHA allows any material—metal, mesh, polycarbonate, or composite—provided it withstands normal use and impact and prevents access to danger zones.

Can a guard be removable?

Yes, guards may be removable for maintenance, but they must be securely fastened during operation and replaced immediately after servicing.

Does OSHA specify guard thickness or type?

No. OSHA 1910.212(a)(2) is performance-based. The employer must ensure that the guard effectively prevents exposure and remains securely attached.

1910.212(a)(3) – Point of Operation Guarding

OSHA 1910.212(a)(3) — Point of Operation Guarding

OSHA 29 CFR 1910.212(a)(3) sets forth the point of operation guarding requirements for machinery used in general industry.

The “point of operation” is the area on a machine where work is performed—such as cutting, shaping, boring, forming, or assembling a part.

This section requires that each machine have a guard or safeguarding device that prevents the operator from having any part of the body in the danger zone during operation.

Purpose and Scope

The purpose of 1910.212(a)(3) is to eliminate exposure to moving tools or dies that can cause crushing, amputation, laceration, or puncture injuries.

It applies to all machines with a point of operation hazard, regardless of size or industry.

Typical examples include presses, saws, milling machines, lathes, shears, and drills.

Key Requirements

- Every machine must be equipped with a guard that prevents the operator from reaching into the danger zone.

- Guards must be designed and constructed to provide maximum protection while allowing the machine to be operated safely and efficiently.

- Special hand tools may be used to handle materials when guarding at the point of operation is not practical.

- Guards must be securely fastened, maintained in place, and not easily removed or bypassed during operation.

- Safeguarding devices such as light curtains, presence-sensing devices, or two-hand controls may be used if they provide equivalent protection.

Examples of Point of Operation Hazards

- Cutting blades or rotating cutters that can amputate or lacerate fingers.

- Press dies or molds that can crush hands or fingers during operation.

- Drill bits, boring tools, or milling heads that can pierce or entangle body parts.

- Shearing or punching points that can sever material—and body parts—with the same force.

Acceptable Guarding Methods

- Fixed barrier guards enclosing the point of operation.

- Interlocked guards that stop machine motion when opened or removed.

- Adjustable or self-adjusting guards that move automatically to block access as material is fed.

- Two-hand controls requiring both hands to activate the cycle, keeping them out of danger.

- Electronic presence-sensing devices such as light curtains or safety mats that halt motion when triggered.

Common Violations

- Operating a machine with missing or disabled point of operation guards.

- Using hand-feeding where fixed or adjustable guards should be installed.

- Removing guards to increase production speed.

- Failure to provide safeguarding when machine design allows operator access to hazardous movement.

Compliance Tips

- Identify all machine points of operation and assess potential contact hazards.

- Install fixed guards where feasible; use engineered safety devices when full enclosure is not possible.

- Inspect all guards before each shift and re-secure after adjustments or maintenance.

- Train operators to recognize guarding deficiencies and to report missing or damaged safety devices immediately.

Why OSHA 1910.212(a)(3) Is Important

Point of operation injuries are among the most severe and preventable workplace incidents.

By enforcing 1910.212(a)(3), OSHA ensures that all machines have reliable guarding or safety devices that keep operators’ hands, fingers, and bodies outside the danger zone during work.

This rule remains one of the most frequently cited machine safety violations nationwide.

FAQ

What is considered the “point of operation” under 1910.212(a)(3)?

It is the location on a machine where work is actually performed on the material—such as cutting, shaping, forming, or drilling.

Can a hand tool substitute for a guard?

Only when physical guarding is not practical. Even then, special hand tools must be designed to keep hands a safe distance from the danger zone.

Do presence-sensing devices meet OSHA’s requirements?

Yes, if they provide equal or greater protection than a physical barrier and prevent any part of the body from entering the hazard zone during operation.

1910.212(a)(3)(i) – Guard Construction and Safety Design

OSHA 1910.212(a)(3)(i) — Guard Construction and Safety Design

OSHA 29 CFR 1910.212(a)(3)(i) outlines the design and performance requirements for point of operation guards.

This provision mandates that guards be designed and constructed so that no part of the operator’s body can enter the danger zone while the machine is in use.

It ensures guards are not merely present, but effective in eliminating exposure to mechanical hazards.

Purpose and Intent

The purpose of this section is to establish functional performance criteria for machine guards, rather than prescribing specific materials or configurations.

The employer has flexibility in choosing a guarding method, but the chosen system must physically prevent entry into the danger zone during operation and must withstand normal working conditions.

Key Guard Design Requirements

- Complete Coverage: The guard must fully enclose or block access to the hazard area where the operation takes place.

- Strength and Rigidity: Guards must be strong enough to resist mechanical stress, vibration, and accidental impact without failure or displacement.

- Visibility: Guards should allow clear observation of the work area when necessary, using materials such as mesh or transparent panels.

- Secure Installation: Guards must be firmly attached so they cannot be easily removed, loosened, or bypassed during operation.

- Usability: The guard must allow normal machine operation, feeding, and maintenance without creating additional hazards.

Examples of Guard Types Meeting 1910.212(a)(3)(i)

- Fixed steel enclosures surrounding the cutting or forming area.

- Interlocked access doors that stop the machine when opened.

- Transparent polycarbonate guards providing visibility and protection.

- Barrier guards with restricted openings preventing hand or arm entry.

Common Compliance Errors

- Using lightweight or flexible materials that can deform and allow contact.

- Guards not secured tightly to the machine or easily removed without tools.

- Guard openings large enough to allow finger or hand access to the danger zone.

- Guards that obstruct visibility or require removal for normal operation.

Best Practices

- Design guards that exceed minimum strength requirements and resist bending or vibration.

- Test guard designs under real operating conditions to ensure reliability and protection.

- Use standardized opening-size tables to determine acceptable distances between guards and hazards based on reach limitations.

- Document guard inspection results and repair or replace any that show wear, damage, or looseness.

- Train operators and maintenance staff on safe use and adjustment procedures for all guarding systems.

Why OSHA 1910.212(a)(3)(i) Is Important

Many guarding failures occur not because guards are absent, but because they are poorly designed or improperly installed.

OSHA 1910.212(a)(3)(i) ensures that guarding methods perform their intended function—keeping the operator’s body completely outside the danger zone while allowing safe, productive operation.

Proper guard design is the first line of defense against amputations, lacerations, and entanglement injuries.

FAQ

What does “constructed so that no part of the operator’s body can enter the danger zone” mean?

It means the guard must be solid or restrictive enough to physically prevent the operator from reaching into the hazard area while the machine is in motion.

Can see-through materials like plastic or polycarbonate be used?

Yes. Transparent guards are acceptable if they meet strength requirements and provide the same level of protection as opaque materials.

Is there a required guard thickness or material type?

No. OSHA does not specify materials or dimensions. The guard must perform effectively and remain in place under all normal conditions of operation.

1910.212(a)(3)(iii) – Guard Design for Operator Safety

OSHA 1910.212(a)(3)(iii) — Guard Design for Operator Safety

OSHA 29 CFR 1910.212(a)(3)(iii) establishes the performance criteria for guard design and construction.

It requires that every machine guard be designed, built, and installed so that it effectively protects the operator from injury during machine operation.

This provision emphasizes that guard design must be functional, durable, and capable of providing full protection throughout the equipment’s use.

Purpose and Intent

The intent of 1910.212(a)(3)(iii) is to ensure that guarding effectiveness is not compromised by poor design or materials.

Even when a machine has guards, operators can still be injured if those guards fail under stress, vibration, or improper installation.

OSHA requires that guards maintain their protective function under all normal operating conditions.

Key Design Requirements

- Strength and Durability: Guards must resist impact, vibration, and deformation caused by routine use and environmental conditions.

- Secure Mounting: Guards must be firmly attached and cannot be easily removed, bypassed, or displaced during normal operation.

- Ergonomic Function: Guards should be designed to allow normal operation and maintenance without creating awkward or unsafe postures.

- Visibility: When feasible, guards should permit observation of the operation to ensure quality and alignment without removal.

- No New Hazards: Guard edges and surfaces must be smooth, free from sharp corners, and designed not to introduce new pinch points or catch hazards.

Acceptable Guarding Examples

- Fixed metal guards enclosing belts, pulleys, and gears.

- Transparent guards made of high-strength polycarbonate for visibility and impact resistance.

- Interlocked access doors that automatically shut off the machine when opened.

- Barrier guards preventing reach into moving parts while allowing visual monitoring.

Common Compliance Issues

- Guards that loosen or vibrate during machine operation, reducing protection.

- Materials that crack, warp, or deteriorate under heat or chemical exposure.

- Improperly designed openings that allow finger or hand access to moving parts.

- Guards that must be removed to complete normal adjustments or feeding.

Best Practices for Compliance

- Select guard materials suitable for the specific machine environment (e.g., metal for impact resistance, polycarbonate for visibility).

- Incorporate secure mounting brackets and fasteners that prevent accidental removal.

- Follow design guidelines for minimum safe distances between guard openings and hazard zones.

- Inspect and test guards periodically for wear, looseness, and stability under normal vibration and operation.

- Document guard designs, materials, and inspections as part of your facility’s machine safety program.

Why OSHA 1910.212(a)(3)(iii) Is Important

Even the best guarding concepts fail if the physical construction is inadequate.

OSHA 1910.212(a)(3)(iii) ensures that all guards are engineered for real-world performance, protecting operators and maintenance personnel from the severe hazards of rotating, cutting, or crushing machinery.

By emphasizing design integrity, this section reinforces the need for reliable, tested, and properly installed guarding systems that remain effective throughout the life of the equipment.

FAQ

What is the main goal of 1910.212(a)(3)(iii)?

To ensure guards are designed and built to prevent operator injury under normal operating conditions, providing long-term durability and protection.

Can a temporary or makeshift guard meet this requirement?

No. Guards must be of permanent construction or equivalent strength, securely mounted, and designed for continuous use.

Do materials matter for compliance?

Yes. Guards must be made of materials that withstand the machine’s operational stresses and environmental factors without failure.

B11 – Machine Safety & Machine Tool Standards

ANSI B11 — Machine Safety & Machine Tool Standards

The ANSI B11 standards series comprises a robust framework for machinery and machine tool safety. It addresses risk assessment, design, guarding, control systems, risk reduction measures, and installation and maintenance of machines. Although not regulatory law, B11 standards are widely referenced by industry and used to interpret OSHA’s machine guarding rules (e.g. 29 CFR 1910.212). :contentReference[oaicite:2]{index=2}

Structure of the B11 Family

The B11 family is organized into three types of standards:

- Type A (Basic Safety Standards): e.g. ANSI B11.0 defines general concepts, terminology, risk assessment, and safety principles. :contentReference[oaicite:3]{index=3}

- Type B (Generic Safety Standards): These address safeguarding methods, performance, or safety aspects used across machines (for example, B11.19—Performance Criteria for Safeguarding). :contentReference[oaicite:4]{index=4}

- Type C (Machine-Specific Standards): Focused on individual machines or categories (e.g. B11.1 for power presses, B11.9 for grinding machines, B11.10 for sawing machines). :contentReference[oaicite:5]{index=5}

Core Themes & Provisions

- Risk Assessment / Reduction: B11 emphasizes identifying hazards, assessing risk, selecting and validating protective measures, and verifying that risk is reduced to acceptable levels. :contentReference[oaicite:6]{index=6}

- Safeguarding Methods: Fixed guards, interlocked guards, presence sensors, two-hand controls, light curtains, etc., are all covered with performance criteria. :contentReference[oaicite:7]{index=7}

- Performance Criteria: Guards and safety devices must meet minimum response times, strength, durability, fail-safe behavior, and integration with control systems. :contentReference[oaicite:8]{index=8}

- Safety in Existing (“Legacy”) Equipment: B11 encourages adaptation of older machines via retrofitting or supplementary safeguarding where feasible. :contentReference[oaicite:9]{index=9}

- Design, Modification & Integration: Covers requirements for design, safe modifications, wiring, control logic, maintenance access, risk during changeover, and system integration. :contentReference[oaicite:10]{index=10}

Relation to OSHA & Enforcement Context

OSHA itself does not mandate ANSI B11 by law, but OSHA’s machine guarding standards allow referencing consensus standards like B11 for technical interpretation. For example, OSHA’s eTool on machine guarding lists ANSI B11 standards as guidance resources. :contentReference[oaicite:11]{index=11}

Many safety professionals use B11 standards to design compliant machine guards and safety systems that satisfy both OSHA rules and best practices.

Common Substandards in the Series

- ANSI B11.0 — Safety of Machinery (baseline, risk methodology) :contentReference[oaicite:12]{index=12}

- ANSI B11.19 — Performance Criteria for Safeguarding (applies across many machines) :contentReference[oaicite:13]{index=13}

- ANSI B11.1 / B11.2 / B11.3 — Press, hydraulic, brake machines :contentReference[oaicite:14]{index=14}

- ANSI B11.10 — Metal sawing machines :contentReference[oaicite:15]{index=15}

- ANSI B11.9 — Grinding machines (ties into OSHA 1910.215 & 1910.213) :contentReference[oaicite:16]{index=16}

Internal Linking & Application Ideas

- Link to child categories like ANSI B11.0, ANSI B11.19, ANSI B11.9 (Grinding), etc.

- Cross-link to your OSHA machine guarding pages, e.g. OSHA 1910.212 General Machine Guarding.

- Link to safety device and guarding product pages: light curtains, interlocked guards, protective covers, control systems.

FAQ

Is ANSI B11 required by law?

No. ANSI B11 standards are voluntary consensus standards, but OSHA and regulatory bodies often use them as authoritative references when interpreting machine guarding requirements. :contentReference[oaicite:17]{index=17}

Which B11 substandard applies to my machine?

Select the B11 standard matching your machine type, such as B11.9 for grinding, B11.10 for sawing, or B11.1 for presses, plus always apply the general rules in B11.0/B11.19. :contentReference[oaicite:18]{index=18}

B11.0 – Safety of Machinery

ANSI B11.0 — Safety of Machinery

The ANSI B11.0 standard (Safety of Machinery) is the foundational “Type A” standard of the B11 series of American National Standards for machine safety.

It is intended to apply broadly to power-driven machines (new, existing, modified or rebuilt) and to machinery systems, not portable tools held in the hand. :contentReference[oaicite:0]{index=0}

ANSI B11.0 provides the essential framework: definitions, lifecycle responsibilities, risk assessment methodology, acceptable risk criteria, and guidance for using Type-C standards in conjunction with this general standard. :contentReference[oaicite:1]{index=1}

Scope & Purpose

ANSI B11.0-2020 covers machines and machinery systems used for material processing, moving or treating when at least one component moves and is actuated, controlled and powered. :contentReference[oaicite:2]{index=2}

The standard’s purpose is to help suppliers, integrators, and users of machinery identify hazards, estimate and evaluate risks, and implement sufficient risk reduction to achieve an “acceptable risk” level. :contentReference[oaicite:3]{index=3}

It also clarifies responsibilities across the machine lifecycle (supplier, user, modifier) and addresses legacy equipment, prevention through design (PtD) and use of alternative methods for energy control. :contentReference[oaicite:4]{index=4}

Key Concepts & Requirements

- Terminology & Definitions: Establishes key machine-safety terms (e.g., machine, hazard zone, safeguarding, risk, risk reduction). :contentReference[oaicite:5]{index=5}

- Risk Assessment Methodology: Describes how to identify hazards, estimate risk severity and probability, evaluate risk, and decide on corrective safeguards. :contentReference[oaicite:6]{index=6}

- Risk Reduction Principles: Focuses on designing out hazards, applying engineered controls, administrative controls and PPE only when higher-level measures aren’t feasible. :contentReference[oaicite:7]{index=7}

- Lifecycle Approach: Applies to design, construction, installation, commissioning, operation, maintenance, modification and dismantling of machines. :contentReference[oaicite:8]{index=8}

- Use of Type-C Standards: ANSI B11.0 explains how to use machine-specific Type-C standards (e.g., B11.9 for grinding machines) together with this standard for full compliance. :contentReference[oaicite:9]{index=9}

Why It Matters

ANSI B11.0 sets the groundwork for safe machine design and use. Without a consistent foundational standard, machine-specific standards may lack coherence or completeness in hazard control.

By following B11.0, manufacturers and users can build robust safety programs, ensure they cover all phases of machine use (including legacy equipment), and demonstrate that hazard identification, risk assessment and risk reduction are performed systematically.

Because the standard is widely referenced by regulatory authorities and industry best practices, compliance strengthens both safety performance and regulatory defensibility.

Relationship to OSHA & Other Standards

Although ANSI B11.0 is a voluntary consensus standard and not a regulation, it is widely acknowledged as “recognized and generally accepted good engineering practice (RAGAGEP)”.

Regulatory bodies like the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) reference the B11 series for technical guidance in areas like machine guarding (e.g., 29 CFR 1910.212) and risk assessment. :contentReference[oaicite:11]{index=11}

Furthermore, ANSI B11.0 aligns with the international standard ISO 12100 (Safety of Machinery — General Principles for Design — Risk Assessment and Risk Reduction) but adds U.S.-specific supplier/user responsibilities and lifecycle responsibilities. :contentReference[oaicite:13]{index=13}

FAQ

Is ANSI B11.0 legally required?

No. ANSI B11.0 is a voluntary standard. However, using it supports compliance with regulatory requirements and industry-recognized best practices.

Which machines does ANSI B11.0 apply to?

It applies to power-driven machinery and machinery systems (new, existing, rebuilt or modified) used for processing, treatment or movement of materials—not hand-held portable tools. :contentReference[oaicite:14]{index=14}

How does ANSI B11.0 relate to machine-specific standards?

ANSI B11.0 defines general safety requirements and methodology; machine-specific standards (Type C) cover detailed safeguarding, controls and machine-type hazards. Together, they ensure full coverage of machine safety. :contentReference[oaicite:15]{index=15}

Z244.1 – Control of Hazardous Energy: Lockout, Tagout & Alternative Methods

ANSI Z244.1 — Control of Hazardous Energy: Lockout, Tagout & Alternative Methods

The ANSI Z244.1 standard (sometimes referenced as ANSI/ASSP Z244.1) provides a detailed framework for the safe control of hazardous energy sources—electrical, mechanical, hydraulic, pneumatic, chemical, thermal, gravitational or stored energy—when servicing or maintaining machines, equipment or processes. :contentReference[oaicite:0]{index=0}

While it is a voluntary consensus standard (not a regulation), it is widely used by safety professionals and referenced in relation to 29 CFR 1910.147 and other machine safety/energy control programs. :contentReference[oaicite:2]{index=2}

Scope & Purpose

ANSI Z244.1 applies to tasks such as construction, installation, adjustment, inspection, unjamming, testing, cleaning, dismantling, servicing or maintaining machines, equipment or processes when the unexpected energization or release of stored energy has the potential to cause harm. :contentReference[oaicite:3]{index=3}

The standard emphasizes the employer’s or machine owner’s responsibility to establish a hazardous energy control program, including procedures, training, audits and alternative methods when traditional lockout/tagout may not be practicable. :contentReference[oaicite:4]{index=4}

Key Elements & Themes

- Energy control program: Program elements include hazard identification, energy-isolation methods, verification of isolation, training, periodic audits, and maintaining a safe work environment. :contentReference[oaicite:5]{index=5}

- Lockout, Tagout, or Alternative Methods: The standard recognizes traditional lockout as the preferred method but allows tagout or other validated alternative methods when risk assessment justifies them. :contentReference[oaicite:6]{index=6}

- Risk assessment & justification: When using alternative methods, a documented risk assessment must demonstrate equivalent protection to traditional LOTO. :contentReference[oaicite:7]{index=7}

- Design and integration: The Z244.1 standard highlights the need for properly designed isolation devices, clear identification of energy sources, controlled transfer of isolation between shifts, and integration with existing safety control systems. :contentReference[oaicite:8]{index=8}

- Training and audits: Authorized employees must be trained, affected employees must be notified, and periodic inspections/audits must verify the program’s effectiveness over time. :contentReference[oaicite:9]{index=9}

Relation to OSHA

Although the standard is not enforceable by itself, Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) recognizes ANSI Z244.1 as a valuable consensus standard for guidance on energy control programs. :contentReference[oaicite:11]{index=11}

Compliance with 29 CFR 1910.147 remains mandatory, and using ANSI Z244.1 can help demonstrate a program meets recognized good practice or “RAGAGEP” (recognized and generally accepted good engineering practice).

Why It Matters

Unexpected machine startup or release of stored energy is a significant cause of serious injuries—including electrocutions, amputations, crushing, burns and fatalities. :contentReference[oaicite:12]{index=12}

Implementing ANSI Z244.1-based programs helps reduce these risks by ensuring controlled isolation of energy sources, validated procedures, trained personnel and audits to ensure ongoing safety.

FAQ

Is ANSI Z244.1 a regulation?

No. It is a voluntary consensus standard. However, OSHA may reference it for guidance, and using it can support compliance with regulatory requirements. :contentReference[oaicite:13]{index=13}

Can we use tagout instead of lockout?

Under ANSI Z244.1, yes—if a risk assessment justifies that tagout or an alternative method provides equivalent protection to lockout. The standard expects documentation and justification when departing from lockout. :contentReference[oaicite:14]{index=14}

Does this standard apply to stored hydraulic or pneumatic energy?

Yes. The standard covers mechanical, hydraulic, pneumatic, chemical, thermal, gravitational and stored energy that may cause harm if unexpectedly released. :contentReference[oaicite:15]{index=15}